At 19, Vievee Francis sat in a bookstore in Detroit and read a poem called “The Child Beater,” by the late poet Ai.

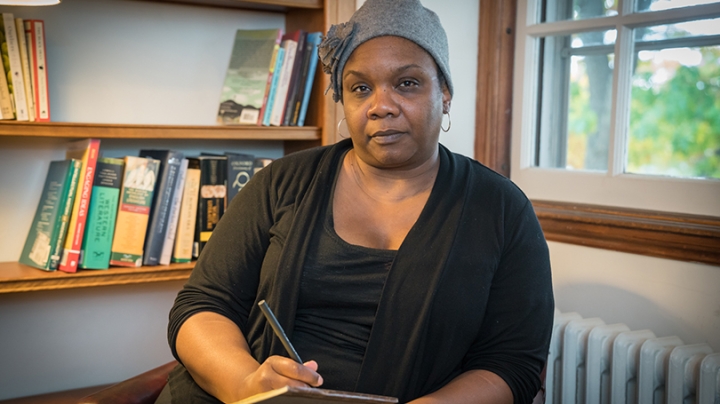

“I just started weeping in the store,” says Francis, who joined the Department of English this fall as an associate professor. “It was one of the most harrowing poems I had ever read. I didn’t know you could write a poem like that—that you could talk about such things. I wanted to be able to do that.”

It was the beginning of her life’s work as a poet. “In that moment I wanted to speak. I wanted to talk about real feelings, real emotions,” she says.

Last week, Francis—an associate editor of the journal Callaloo who has taught as visiting faculty at Warren Wilson College and North Carolina State University—won the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for Poetry for her third collection of poems, Forest Primeval.

The award, named for two of the greatest African American writers of the 20th century, Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright, “honors the best in Black literature in the United States and around the globe,” according to the Hurston/Wright Foundation website.

“The award confirms what Vievee’s colleagues and of course her readers already know: that she is one of the most important and influential poets writing today,” says Andrew McCann, professor of English and chair of the English department.

Of receiving the award, Francis says, “It feels like getting love from home. I was up against incredible writers, and to even be in that company meant a great deal to me. My work pushes up against the boundaries of what may be deemed African American work; there are some transgressions. That the work was received and taken in and given that kind of breath makes me happy.”

“Absolutely Nothing Was Pastoral”

In Forest Primeval, Francis embraces what she calls the “antipastoral” poem. “The book began really as a means of me negotiating living in a forest,” she says. After spending most of her life in Detroit, Francis had moved with her husband, the poet Matthew Olzmann, to western North Carolina, outside of Asheville.

“I felt, coming from Detroit, that I was a pretty strong person, but I was terrified of everything: the bears, these insects I’d never seen before that seemed to come over the mountains like locusts and then suddenly disappear,” she says. “Everything was terrifying; absolutely nothing was pastoral. Nothing was romantic for me. Everything bit, or could bite.”

That sense of alienation from the landscape led her to consider the tradition of pastoral poetry. “I felt like I had something to say back,” she says. “I wanted to talk about how raw and terrifying things were, as opposed to gentling it. I wanted also to talk about how the wilderness around me was unraveling me, and in that unraveling there was a kind of mirror of the wilderness within.”

The collection opens with the line, “I want to put down what the mountain has awakened.” But ironically, she says, part of what her poetic exploration of her new surroundings awakened is a love of mountains. “Now I find it difficult to not be in the mountains. I really feel as if something was altered in me. Something opened up.”

Moving to Hanover, at the northern end of the same Appalachian chain where she lived in North Carolina, feels of a piece with that transformation, Francis says.

Her first book, Blue Tail Fly, is a collection of persona poems in the voices of freed slaves, soldiers, and other ordinary outsiders who lived in the era between the Mexican American War and the Civil War. Her second book, Horse in the Dark, which won the Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize, is more directly personal, focused on her early childhood experiences on her grandmother’s farm in the Piney Woods of East Texas, where she felt a closeness to animals and the natural world that she lost when she later moved with her family to Detroit.

“When I was young, I played innocently. I didn’t consider what it meant to be in the field,” Francis says. “But as an adult black woman to recall enjoying the field, but to know the history of fields, and how black women are often viewed in bestial terms—I began to ponder how much of me is informed by external elements. How much of what I see myself to be is a product of just the joy of my childhood? How much does society and its cruel vision impact me?”

In Forest Primeval, she says, “I’m ready to discuss myself in other terms, and kind of move my explorations forward and out into the world again.” Francis is now at work on a fourth collection of poems, as well as a memoir.

“A Foundational Art”

This is her second stint at Dartmouth—she was a visiting lecturer in creative writing last fall. “I loved my experience here,” she says. “I have a silly grin on my face because of how much I loved it. My students really dove in and I appreciated that, and my colleagues were so engaged with their scholarship—every conversation was inspiring and motivating. It is quite an honor to be able to come back.”

This term, Francis is teaching a “Writing 5” section with first-year students. In the winter, she will be teaching “Ruins, Remains, and Repair,” a seminar comparing the poetry of two industrial cities, Detroit and Krakow, Poland. “I bring a passion to my teaching,” she says. “I love poetry. I don’t know if I’m able to articulate—even within my poetry—how much I love poetry. And I think my students see that. I utilize poetry in almost every aspect of my life.”

Poetry, she says, is “a foundational art. It precedes the novel. It precedes the essay. And as such, all writing is served by the study of poetics.” Everyone needs poetry when other means of communication fail, she says. “We don’t live life on the surfaces. We have to go underneath, and poetry—the lyric poem in particular—forces us to look at the emotive self and what that means.”

On Thursday, Nov. 3, Francis will introduce Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gregory Pardlo, whom she has invited to Dartmouth as part of the English Department’s Poetry and Prose series. Pardlo will read from his work at 4:30 p.m. in the Wren Room in Sanborn House.

Francis says Pardlo “is writing at the edges. He allows himself to be vulnerable, to respond to his world on his terms. He can’t be boxed or stereotyped. He is both a scholar and a poet, so some of the most fun—and there’s actual fun in his text—are poems in the form of course descriptions. I think students will deeply enjoy him.”

Pardlo’s work is part of a shift Francis sees in contemporary poetry, particularly among African American poets. “I don’t think there’s a term for what’s happening yet, but there’s an exploration of the interior that is so piercing, that is really looking at the interior of black lives. I think this is an incredible moment,” she says.

“This is really the first time in American poetry history where everyone is sitting at the table together. We are learning about each other. And we aren’t speaking for each other—we’re letting people speak for themselves, identify themselves as themselves on their own terms, and we’re having to listen to each other. And that is changing all of us.”